By Jessica Dello Russo

In the final months before the community news project, www.northendwaterfront.com, enters a new phase as a treasure trove of archival material on the North End and Waterfront neighborhoods of Boston for many generations to come, I wanted to share with readers a delightfully unexpected follow-up to a series of articles I wrote for the website two years ago (part 1 and part 2). Under the heading “Brethren, Bethel, and Basilica,” the posts described historic houses of worship in and around North Square from the seventeenth to early twentieth centuries, including many church buildings that no longer exist or have been dramatically altered, often for other uses (climb the stairs in the North End/Waterfront Health Center to get an idea).

The series’ focal point was the mission church of my childhood, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, at 12 North Square, which is still standing, though apparently, by order of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston, public Masses and service programs like Alcoholic’s Anonymous ceased to be held in the building nearly two years ago, for reasons still unclear. I live a few blocks from North Square, and invariably, as I pass through, I see people in front of the church trying to figure out if it is open (obviously, I am omitting the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic from this observation, during which time all churches in the North End were closed).

To be honest, I don’t imagine everybody doing so is looking to attend Mass. A good part of the traffic flow through the square is from travelers on the Boston Freedom Trail, a self-guided itinerary that runs from the Boston Common to the Navy Yard and Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown. It criss-crosses the North End to include Paul Revere’s House, Saint Stephen’s Church, Old North, and, of course, the focal point of settlement in this area from the early 1630s, decades earlier than anything else on the neighborhood map, right at North Square.

In a dramatic remodeling in 2018, the square’s almost four hundred years of history (native settlement prior to that date is not conclusive, but being so close to the natural waterline, there was surely a human presence in the North End long before its European colonization) were memorialized by the installation of four sculpture groups in bronze by the art coop A+J+ Art and Design. It’s interesting that there are two features of the square worked into all the historical eras depicted in the public art display: the focus on commerce and community gatherings. It’s no wonder, then, that people take notice of the church building. It is what one would expect as the centerpiece to a historic square.

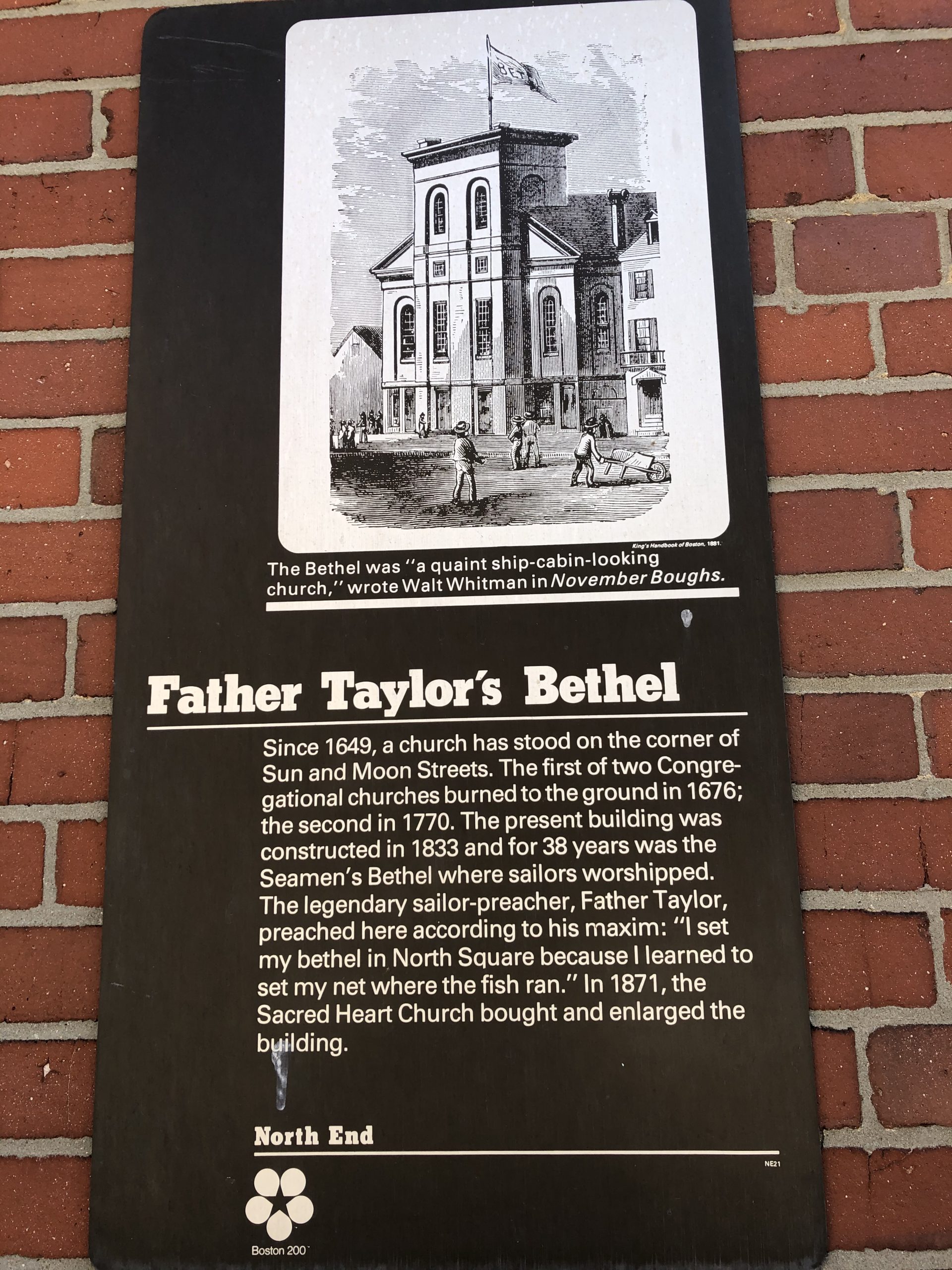

The real “Freedom Trail” church on the square, dating the Colonial era, is a plaque on the building next to the entrance to Mama Maria’s. The standing church on the eastern edge of the triangular-shaped square is a post-Colonial feature, but not that much later: it was under construction as the Boston Seamen’s Bethel by 1832, and preserves strong architectural features in the Federal style intermingled with an older Georgian-era meeting house building plan (the Baroque curves on and around the original belfry and statuary are later additions: the structure was seen as “old fashioned” even when new).

In fact, the facade of the building displays several plaques describing the building’s long service history and significance to the North End. These signs were there when I was a child, though at the time I was not particularly aware of what they said. The most official looking was a metal panel put up in the year of the USA’s bicentenary in 1976. At some point, I must have been outside waiting for my family at the end of Mass and killed time by reading what the sign said, just like the tourists always did. That is how I first made the connection between my parish church, Sacred Heart, and the Seamen’s Bethel of Fr. Edward Thompson Taylor.

One of the challenges I faced writing about Fr. Taylor and his mission for “Brethren, Bethel, and Basilica” touches upon a matter very much in discussion among historians today: namely, recognizing the formation of a historical narrative as a specific identity construction. In concrete terms, take the Boston Freedom Trail, set out in the 1950s during construction on the old double-decker highway to specifically mark surviving Colonial-era sites amidst mid-twentieth century urban terrain. It was impossible to arrange the path chronologically, but the focus was on reconstructing the “lost Boston” of Sam Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere.

The timing of the initiative coincided as well with the government-approved mass demolition of building blocks in several immigrant neighborhoods of Boston’s downtown. A good number of these, though by no means all, were material testimonies of Fr. Taylor’s Boston from the first half of the nineteenth century, before the start of the Civil War. To expedite urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s, the physical remnants of this era were not seen as historically compelling to feature in tourist guides (today, the Harbor Walk and “Walk to the Sea” are good places to start learning about Boston’s maritime past, but are dedicated almost exclusively to the commercial aspects of sea trading).

Architecturally speaking, what we mostly see in the North End of today are Colonial building islands amidst a sea of tenements from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The area’s current “Little Italy” identity is tied to the building history of the later era that warehoused cheap immigrant labor to Boston’s instustries and manufacturing plants.

Reflecting on what Boston as a city has chosen to preserve of its past helped me to understand why the Freedom Trail passes over Taylor’s bethel. The building is not a pristine survivor of an earlier age, but a well-used and much beloved community institution for nearly all of its one hundred and eighty-eight years: on this point, it’s safe to say that I’m an authority, since my own family has been involved in the life of the institution for a good part of this time (as members of the Saint Mark’s Society that bought the building from the Port Society in the early 1880s).

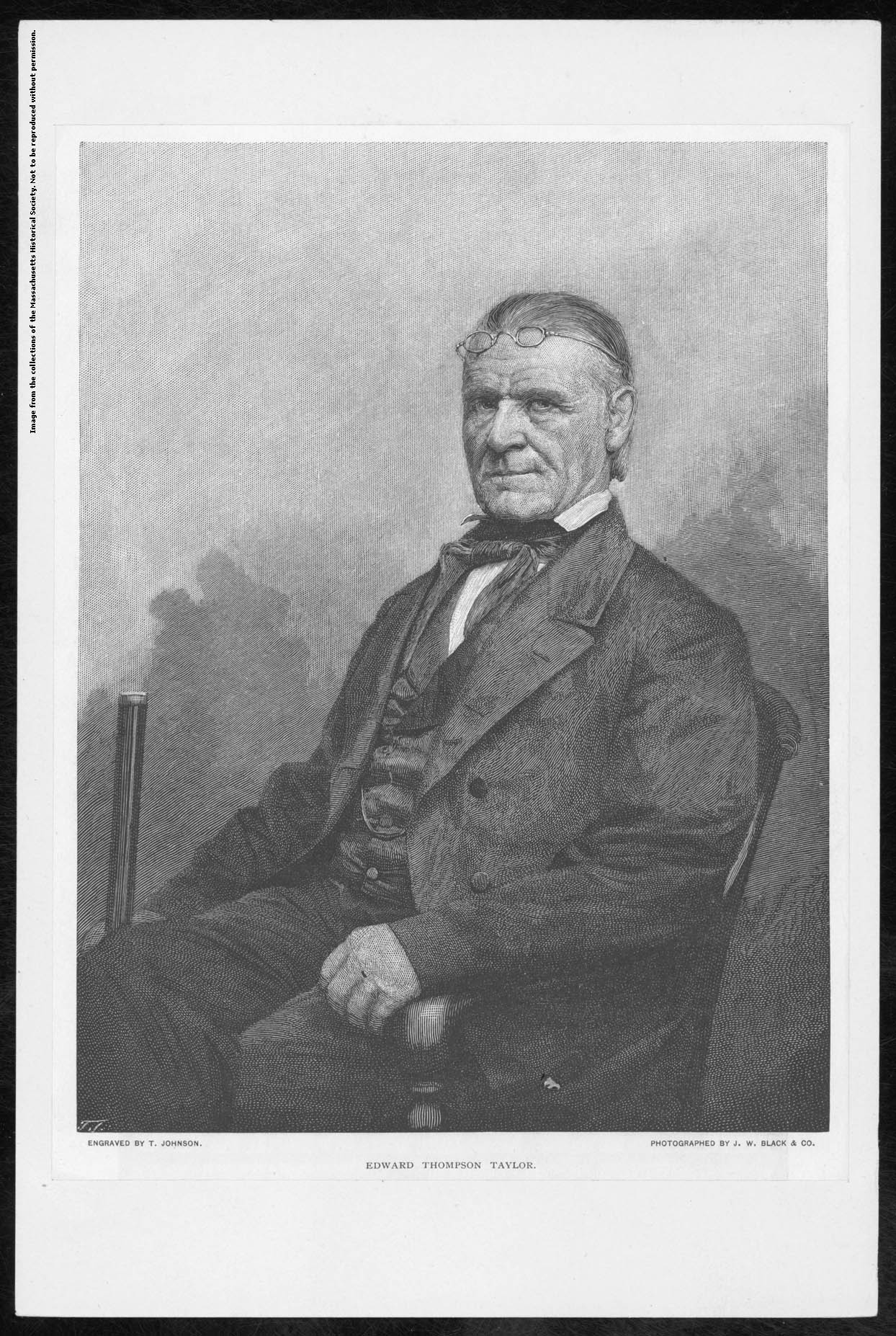

In a state of uncertainty over creating an accurate description of Taylor’s North End, I could not expect much help from Fr. Taylor himself. Taylor was more or less functionally illiterate—he found it very hard to read and write and had others do these tasks for him. He published no books, not even a collection of sermons, a literary genre which, believe it or not, was often read as self-improvement.

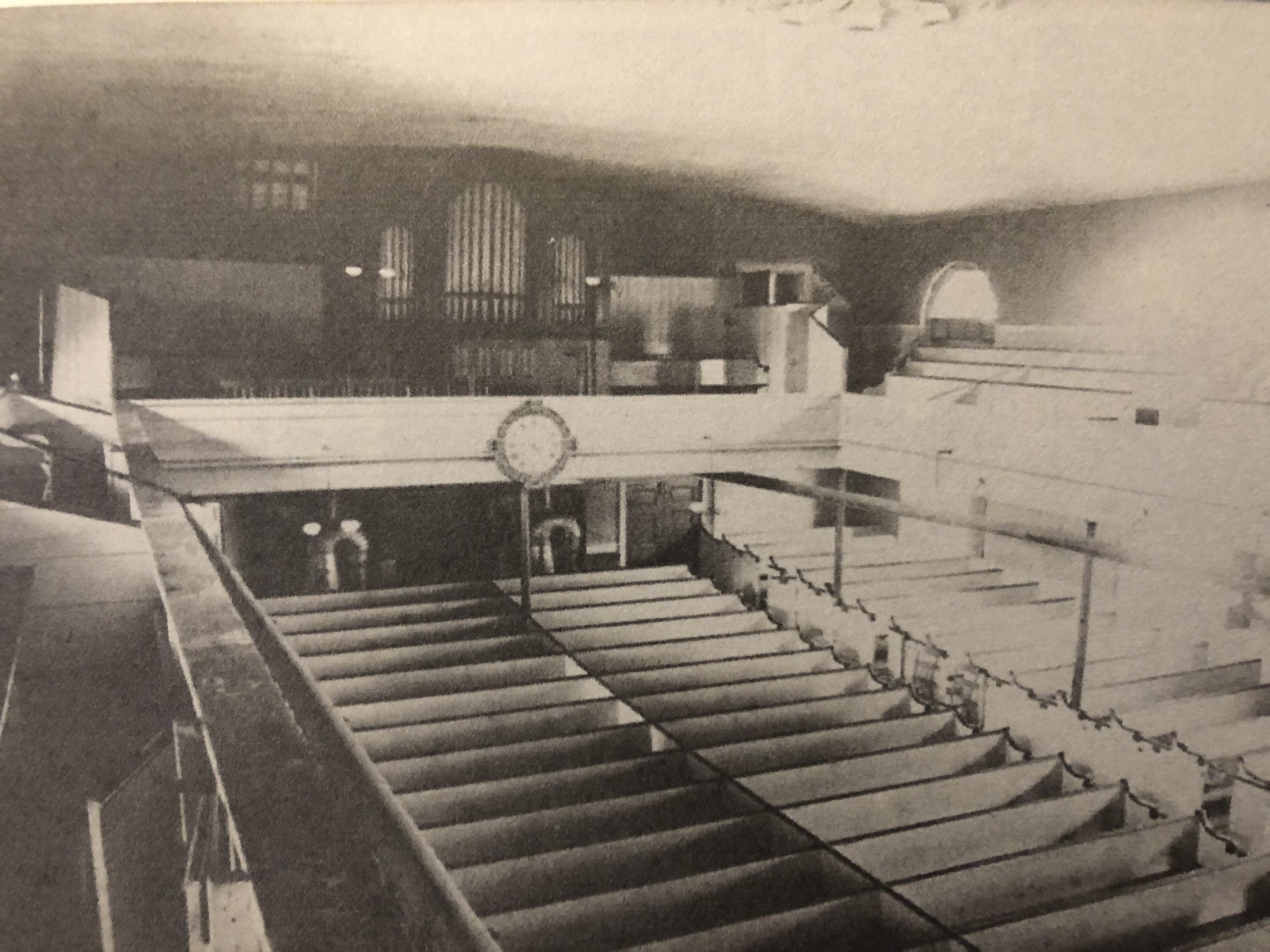

I ended up picking up my archaeology tools and hunting down old maps and images, building relics, and other evidence of the original structure in its current state. I knew from these that the nearly forty-year mission of Taylor from 1829 to 1868 was not only a community fixture, but also an international sensation: the upper hall of the bethel (the term used for the meeting places of a global mission to seamen) could fit over a thousand people, and the lower story was used for storerooms, shops, a free reading library, nautical classes, a children’s schoolroom, and a nineteenth-century precursor to Alcoholic’s Anonymous, though many community functions also spilled over into the Mariner’s House nearby (old-school North Enders might ask: where did they play Bingo? The answer is they didn’t, gaming was not allowed). But what was the secret of Bethel’s success among the North End community? Who could speak up for it, if not Taylor himself?

The question is largely resolved by a new collection of witness accounts to Taylor’s life compiled with remarkable precision and accuracy by the Rev. William H. Armstrong (Amazon, 2020). When Armstrong first alerted me to the publication of his book after reading my articles in www.northendwaterfront.com, I imagined it to be a fairly slender volume: after all, Taylor’s own paper trail is, well, paper-thin. I was amazed to receive, instead, a five-hundred page publication of source material, arranged chronologically. It not only provides insights into Taylor’s activity not included in most biographical accounts (though recent studies have made strides in filling the gap), but also illustrates the curious web of social connections between Bostonians in that time.

Taylor worked in a non-denominational capacity for the Port Society of Boston, and one issue underscored throughout the book is that the doctrinal issues dividing Boston’s Protestant congregations were largely put aside, exceptionally, in order for this community outreach to work. In a brief, but eloquent introduction, Armstrong points out that Taylor, an ordained Methodist minister, freely fraternized with, and publicly praised the Unitarians, perhaps out of moral principle, but also because they had deep pocketbooks and economic interests on Boston’s wharves.

Contrary to society practices of the time, the North Square Bethel congregation was an open one (not fee-based) and had no dress code or denominational affiliation aside from preaching a normative Christianity. The seating arrangement had sailors in the seats of privilege at front and center, people in city society and their guests in the side aisles, and others in the galleries. Unfortunately, one social norm that Taylor did not overturn, as he should have done, was the segregation of Blacks at the back of the church, a regulation over which other liberal Boston congregations had split apart. Armstrong makes clear that Taylor was no friend to abolitionists, whose combative approach he disliked (though his own children engaged publicly in the anti-slavery movement before the Civil War: it is possible that Taylor even met John Brown while Brown was lodged with Taylor’s daughter, Mary Ellen Russell). Black attendees nonetheless could speak out during services like any worshipper could, and seem to have made up a notable part of the audience each Sunday.

Taylor welcomed a diverse population through his doors, including the despised Roman Catholics, “heathens” from foreign lands, sailors who were Arabs, and those who were Jews (to clarify, church attendance was a social occasion—in some ways, not so different from the talk show of today—and sailors of all denominations felt free to accompany comrades to these gatherings, especially since Taylor put on a good show and not only on the Bible). With almost no formal schooling, Taylor still found a way to speak to all nations, dropping Talmudic sayings into his sermons as well as observations on the geography and politics of foreign lands.

With the seamen came their families (if based locally) and other social connections: all in all, the Bethel reflected the Boston emerging in the industrial age: bustling with business, bulging with people, and building on an unprecedented scale to that time: very soon the city’s church steeples would no longer dominate the skyline, but, for now, they seemed to blend with the ship masts to make a forest of the Shawmut peninsula once more. Taylor chose not to hang a bell in his square tower (funds were not always available for a steeple, and, in fact, the large window made the space well suited for a sail loft and community attic), erecting, instead, a tall mast as a flagpole and hoisting the American flag or Bethel flag in blue as the call to prayer. It would have been visible to the ships entering Boston Harbor, and was, indeed, the safe harbor that many chose.

In putting this collection of reports on Taylor together, Armstrong realized that an important voice was missing: that of the sailor. Like Taylor, the bulk of his congregation left no account of the bethel. The lands people’s reports, many of which are by women, include multiple accounts by one time fellow North End minister Ralph Waldo Emerson, as well as those by Nathaniel Bowditch, Charles Dickens, the Peabody sisters, and Horace Mann. But on the whole they remain literary sketches of the man and his singular approach to Christianity.

Nonetheless, there are glimpses of the North End community whom Taylor principally served. We learn that the high mortality rate for infants depressed him: he often buried several in one week. Liquor producers and distributors ran a smear campaign against his temperance crusade, aided and abetted by some local politicians. Many neighbors were lodged in makeshift rooming houses with few regulations for health and safety. People from the nicer parts of the city drove on the main streets to his meetings because they were afraid to be in the neighborhood.

But Taylor himself was proud of being a long time resident of the North End in a brick town house at the corner of North Square and Moon Street, where the wooden dwelling of another great North End minister, Cotton Mather, once stood (roughly the site of Crosstown Arts today: a nice detail is that some of the old oak from Mather’s building seems to have been reused for the beams in that which housed Taylor). One of his closest neighbors and a good friend was the Roman Catholic priest Fr. George Foxcroft Haskins, director of the House of the Angel Guardian (on the site of St. John’s School). When a visitor spoke disparagingly of the area because of its proximity to the “Black Sea” of grog shops and brothels, Taylor demanded that they go outside the bethel and take a look around at the houses of the good folk which surrounded the square, including neighbors who were Irish, Portuguese (a language Taylor had picked up while at sea), and Black. I am happy to report that thanks to Armstrong’s book, we have confirmation that already at that time the North Square resident pigeon flock was dive-bombing pedestrians! And, yes, Taylor had to deal with the rat problem as well.

I could continue to reveal the portrait of the neighborhood and an era which emerges from Armstrong’s book, but I strongly recommend you obtain a copy of it for yourself. It is a valuable source book for further work on a variety of historical and theological issues, and makes a compelling case to make Taylor’s legacy better known. A memorial plaque outside of his Bethel is clearly not sufficient: I feel that Taylor would prefer to see open doors.

The book, Father Taylor, Boston’s Sailor Preacher: As Seen and Heard by His Contemporaries, edited with introduction by William H. Armstrong (Amazon, 2020), in kindle or print, can be purchased here.

Jessica Dello Russo is a native North Ender and daughter of regular NorthEndWaterfront.com contributor Dr. Nicholas Dello Russo. She is also a graduate of the Vatican’s Institute for Archaeology.

My great great grandfather, Charles L. Mowatt, a seaman, lived his later years in the North End. Charles was stationed on schooner Sallie Baker (among others), and at Emerson’s and Green’s wharf. About 1885 Chas. Mowatt began to attend the Bethel Church in Boston and on 4/19/1891 Charles was admitted to the church and baptized. In 1889, John Welch, 3 Salem Ct, Boston, missionary at the Baptist Bethel Church, meets Charles Mowatt at the church. John Welch’s deposition in support of Mowatt’s application for a widow’s pension calls Mowatt’s burial place the Sailors Lot at Woodlawn Cemetery, owned by the Lady’s Bethel Society. He said he was intimately acquainted with Mowatt for 5 1/2 years prior to Mowatt’s decease “and he resided in (sic) my family.” except when he made voyages on coasting vessels [twice?] as Cook and Steward. Mowatt told him he was French, and he appeared to be so to Welch. Mowatt said he was in the US Navy many years before and during the Civil War. [This was verified by his military records and affidavits in support of his pension]. Mowatt was living at No. 6 North Hudson (?) St. with George Tutto (?) Futto (?) when he died.

In his pension application he states that his residence is 3 North Bennett Court, Boston, Mass. Close in time, he was listed as Chas. Mowatt US Navy Boston Mass. of 172 Commercial St, Boston, Mass. April 23, 1891. On 11/20/1891, he signed Charles Mowatt 332 Hanover St, Boston, Mass. On 1/12/1893 Charles Mowatt, 3 Salem Court, Boston, MA, Seaman, Boatswains Mate (crossed out) Ohio, Paul Jones, US Navy. Rate $6 per month commencing Jany 21, 1891. Disabled by rheumatism approved for admission. $6.00. No other pensionable disability. 11/24/1897 Charles dies at City Hospital, Boston, on Thanksgiving day. Mr. Nathan A. Fitch, minister, called to identify body. Gives Charles decent burial in the Phineas Stowe seamen’s lot at Woodlawn Cemetery. John Welch’s deposition calls it the Sailors Lot, owned by the Lady’s Bethel Society. Welch, of 3 Salem Ct, Boston, said he was intimately acquainted with Mowatt for 5 1/2 years prior to Mowatt’s decease “and he resided in (sic) my family.” except when he made voyages on coasting vessels [twice?] as Cook and Steward. 12/13/1897 Application for Reimbursement. “I, Nathan A. Fitch, do swear that Charles Mowatt, late resident of Boston, County of Suffolk, State of Mass. died on the 24th day of November, 1897, that the deceased drew a pension at the agency at __ under certificate no. 19,592 up to the 4th day o Sept. 1897, as the Seaman, US Navy of USS Ohio & Paul Jones, formerly sailor, in the service of the US; that said decedent left surviving no widow and no child under the age of sixteen years, and did not leave sufficient assets to meet the expenses of decedent’s last sickness and burial; and that said expenses are correctly enumerated in the following statement, the names of the persons who rendered service or furnished necessaries being given, with items and amounts: J. W. Sprague, Undertaker, Paid $39.00….There are no other outstanding bills….claiming the sum of accrued pension…The decedent left no property whatever..The decedent’s last sickness continued uninterrupted from Nov 13, 1897 to date of death, and its nature and degree were as follows: Sclerosis, chronic nephritis, hypotrophed? heart. The pension certificate is herewith was surrendered U.S. Pension Agent at Boston. My residence is at No. 40, on Franklin Street, in the Town or City of Somerville…Mass., and my Post Office address is #10 New Fanuel Hall Market, Boston, Mass. Applicant’s signature: Nathan A. Fitch. We, Benjamin F. Briggs and John Welch, neighbors of Charles Mowatt, … hereby declare that we know the same to be true. Signed Benjamin F. Briggs John Welch and sworn the 13th day of December 1897 at Boston, Mass.” Pensioners certificate must be forwarded with claim to the ?? Department State House Boston. 6/5/1900 Deposition of Nathan A. Fitch, aged 63 years of New Hay Market, Boston, occupation Poultry dealer. “I first knew Chas. Mowatt about 1885 when he began to attend the Bethel Church in this city. He appeared to be a sea fairing man. He was later taken in to said Church as a member. I saw said Mowatt occasionally until his death in Nov. 1897, and he attended said said Church very regular. He would stop with John Welch usually when in the City. Said Welch is clerk of said church. I do not recall that Mr. Mowatt ever told me any thing a out his life history or that he had been married. Don’t recall that I ever talked with him about his early life. Do not know where he was born. Never knew that he was married until after his death. I was informed that he was sick in the City Hospital, but was not able to go & see him. At his his death I went to the hospital and had the body decently buried otherwise he would have been buried in a paupers grave. And as he had informed me that he served in the Navy a long time, I did not think it proper that he should be buried that way. He was a genial man. I never saw with any woman. Never heard that he lived with any woman. I paid for the funeral services and received reimbursement from the government for expenses. After his death and burial I received a letter from his daughter in Carlisle, Mass. thanking me for my services. I have never met the daughter & have forgotten her name. I am positive that Mowatt was not living as a married man while I knew him as stated. I have never seen his widow. He never told me that was not married. I do not know on what ships he sailed. While I knew him or while in the service. I would refer you to Mr. John Welch, 330 Harrison St. Bethel Ch. This deposition is correctly recorded. Nathan A. Fitch”

6/6/1900 Deposition of Bernhard Johnson, 50 years of age, 111 Frances St, East Everett, Mass. Occupation, Sexton of the Bethel Church Mission. footnote.com/image/29009163. “I first knew Chas. Mowatt sometime in the eighties when he came to the “Bethel Church” in Boston, Mass. He was a sea faring man, sailed on Coastline Vessels as cook. He joined said church and was a constant attendant when in the City. He lived with John Welch three or four years and was at the Seaman’s Home 8 North Bennet?? St a while. I talked with him about his life. He told me of a long service in the Navy through the civil war. That he married at some time. Did not say to whom he was married, said he was not living with his wife, said his wife resided in Lowell, Mass. Did not say when he separated from his wife. He never spoke of having been married more than once. Spoke of having children: a son named “Ruber” who was a civil engineer came to the Bethel once to inquire after him. Mowatt was known as Chas Mowatt. Never knew he had a “middle name”. He said he drew around a thousand dollars in a lottery and purchased a vessel and the vessel was sunk at sea. He spoke of owning a farm at some time: he never spoke of being divorced from his wife. Never spoke of but one marriage. Don’t know where he married his wife: he went to Lowell, Mass. several times while I knew him. He was of French descent. He told me that he was born in the “old country”. Never heard him speak of Baltimore, Md. or of being born there. Never heard him speak of his parents or relatives, except his children. He was never living with a woman while I knew him. His habits were good. He was a ?? frusiman? gentleman? This deposition is correctly recorded. Bernhard Johnson.”

6/7/1900 Deposition of George H. Tuttle, 37 years of age, 15 Marshall St, Boston, MA. “I first knew Chas. Mowatt in the Eighties – before 1889. Before he joined the church. He was a seagoing man and went as Stewards Cook on Coasting Vessels. During the last years of his life he boarded at my house – was taken to City Hospital from my house about a month before he died. He was a pensioner? and spoke of having a wife. Don’t know whether he was separated from his wife. He never said much about her. Said he had a son who was a civil engineer. Don’t know his name. Never heard him say where he was born. Don’t know his nationality. He told me that he owned a vessel once but did not say where he owned it. He got the title of Capt. while he owned the vessel and we called him “Capt. Mowatt.” Said he lost the vessel. While I knew him he never lived with any woman. John Welch of the Bethel Church kept him usually when in the city for three or four years before he came to my house. When he was taken to the hospital, the Drs asked him who should be informed if anything serious happened and he gave them my name saying “These folks are all the friends I have.” meaning me and my stepfather Harry Smith. I never heard Mowatt speak of his wife or that he was divorced or whether his wife was dead or living. This deposition is correctly recorded. George H. Tuttle.”

6/7/1900. Deposition of Harry Smith, 66 years of age, 15 Marshall St, Boston, Mass. Occupation Janitor. “ I first knew Chas Mowatt in the eighties cannot give date. Saw him first while attending the Baptist Bethel in this city. Never knew him as Chas. L. Mowatt. We always called him “Capt. Mowatt.” He lived at the house of myself & stepson Geo H. Tuttle about a year before his death and was taken from our house to the City hospital about a week or so before he died. He spoke of having been married but to who, when or where I never knew. Said his wife was living in Lowell, Mass. Don’t know where he was born or anything about his relations except he had a son and two daughters and was not living with his wife. He was not divorced to my knowledge. Never said much about his family affairs to me. HIs habits were good. He was not living with any woman while I knew him. He drew a pension. Said his son was a civil engineer. When able Capt. Mowatt went on voyages on coastline vessels from this part as Steward or Cook. I know nothing of his early life. When he was taken from our house to the City Hospital he told the Dr. who came after him in answer to the question as to who he would have notified in case he should die – “These are the only friends I have” referring to myself and Geo. H. Tuttle my stepson. This deposition has been correctly recorded. Harry Smith”