This is the fourth installation of Nicholas Dello Russo’s “A Shtetl in the City”, following part one, part two, and part three.

My name is Solomon Levi,

At my store in Salem Street,

There’s where you’ll find your coats and vests,

And ev’rything else that’s neat:

I’ve second-hand Ulsterettes,

And ev’rything else that’s fine;

For all the boys they trade with me,

At one hundred and forty-nine.

This street song is almost totally forgotten today, but one hundred and twenty five years ago it would have been easily recognized by most Americans. It was included in many song compilations along with such famous tunes as “America the Beautiful”, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and the songs written by Stephen Foster. I even remember singing it in the North End Union when I was a child in the 1950s. It can be found in at least two compilations of songs given to Harvard College undergraduates because for decades Harvard students came to the North End to shop for inexpensive casual clothes on Salem Street. When I was in college in the 1960s, my favorite outfit, mostly obtained in the North End, was chino pants, a madras shirt and tan buckskin shoes (dirty bucks). The shoes came from Harry Sandler’s shoe store on Union Street.

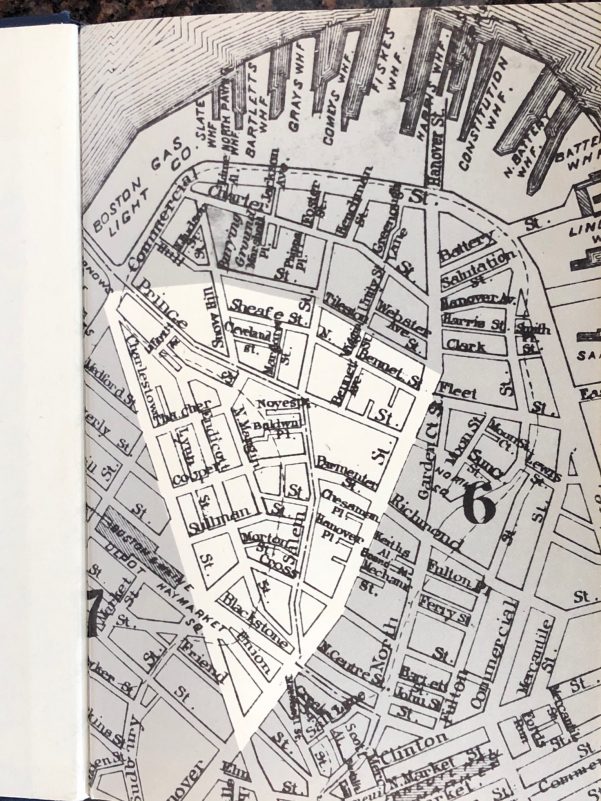

The song had many iterations, some mildly offensive, but most innocuous. There’s even a Klezmer version sung in Yiddish. The song tells the story of Solomon Levi, a Jewish merchant who had a dry goods store at 149 Salem Street at the corner of Prince Street. For at least two generations after the Civil War the triangle bounded by Hanover, Prince and Charlestown (North Washington) Streets was the center of Boston’s Eastern European Jewish life and culture. Up until the 1970s Salem Street was lined with Jewish-owned shops. Sheldon’s, Clayman’s, Meyer’s, Etta’s, Jack’s, Resnick’s and many others. These shops existed side by side with Italian grocery stores and formerly Kosher meat markets which were co-opted by Italian butchers.

In 1960 Rabbi Arnold Wieder received a grant from the Ethel Bresloff Fund to interview the last surviving Jewish residents who emigrated to the North End at the end of the nineteenth century. Brandeis University published a small book containing their reminiscences in1962. The title of the book is The Early Jewish Community of Boston’s North End and it gives a fascinating glimpse into what day-to-day life was like in the Jewish North End. The people Rabbi Wieder interviewed were very old, their average age was 79, and they mainly spoke Yiddish. He was able to gain their confidence because he also spoke Yiddish as well as Hebrew and had been in the concentration camps during World War II. I found this very interesting because I wanted to compare the Jewish experience with that of the Italians. There are many similarities between the experiences of the two groups, but also some interesting differences.

There has been an important Jewish presence in the North End since Colonial times. The first recorded North End Jew was Moses Michael Hays who was Grand Master of the Massachusetts Masons. The assistant Grand Master of his lodge was another local resident named Paul Revere. German Jews began arriving in Boston around the time of the Civil War and settled in the South End where there was also a Christian German community. They assimilated easily into mainstream American life and were mostly businessmen who came from the cities of Germany and Austria/Hungary. Around 1870, eastern European Jews began leaving the shtetls in the Pale of Settlement of the Russian empire. Many of them originally wanted to go to Israel or the United Kingdom, but because of the vagaries of steamship routes and missed opportunities some ended up in Boston.

Rabbi Wieder of course wanted to know why they left Russia and there were two main reasons. The early arrivals left to avoid their sons being conscripted into the Tsar’s army which was essentially a death sentence, but the widespread anti-semitism of the 1870s following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, gave them a great incentive to leave. One of my friends told me his grandfather had a lifelong fear of hearing hoofbeats because he associated it with the Cossacks coming to his village to murder and pillage.

Unlike Italians, Eastern European Jews did not have an agrarian history, farming was not part of their heritage. They were mostly small shop keepers and tradesmen and they transferred these occupations to the new world. Tevye, in Fiddler on the Roof, was a milkman and many of the new arrivals were tailors, shoemakers and tradesmen. Peddling was the most common occupation and most new immigrants who didn’t have a trade would “take a basket” as soon as they arrived. Several dry goods on Salem Street would extend credit to them and they would try and develop a trade route. Many of the men would leave the North End on a Saturday evening and not return until the following Friday night for the sabbath meal, which was invariably chicken. This preoccupation with work changed the family dynamic in very important ways. Life in the shtetls was centered around the synagogue and the Torah. The man of the family was responsible for educating the children, studying the Torah and all charitable activities. In America, these duties were taken over by the women who became much more assertive both in the home and the synagogue.

Life in the North End wasn’t easy, but many of the elderly former residents told Rabbi Wieder how much they loved living there. When the early Jews arrived the North End was mostly Irish, but by the 1890s Italians began arriving in droves. Rabbi Wieder relates a story about a Jewish physician who was walking down Salem Street to attend a home birth. He noticed three young men coming toward him – a Jew, an Irish boy and a black (possibly a Southern Italian), having an animated conversation in Yiddish.

Wieder ends his book with lists of successful North End Jews who became prominent in mercantile and philanthropic pursuits. The actress Sophie Tucker lived at 22 Salem Street. When he was a student at Harvard, Bernard Berenson would bring his classmates to his mother’s deli on Salem Street for a good Jewish meal. Three of the first five presidents of the Beth Israel Hospital were from the North End and many prominent synagogues were started by North Enders including Temple Israel and Temple Ohabei Shalom. An honorable legacy from one small, disadvantaged triangle in Boston.

So what about our friend Solomon Levi and his dry goods store? The second verse of the song tells how he dealt with the ever persistent shoplifters:

But when a bummer comes inside

My store in Salem Street,

And tries to hang me up for coat

And vest and pants complete,

I kicks that bummer out of my store.

And on him sets my pup,

For I won’t sell clothes to any man

That tries to hang me up.

Nicholas Dello Russo is a lifelong North Ender and columnist. Often using vintage photographs, Nick tells the stories of growing up in the North End along with its culture and traditions. It was a time when the apartments were so small that residents were always on the streets enjoying “Life on the Corner.” Read more of Nick’s columns.

I believe the Russian Jews that ended up in Palestine region were agrarian from Russia. The Rothschild family in France fearing that growing influx from Eastern Europe would fuel antisemitism looked to channel these people to Ottoman empire where they were able to purchase land from the Ottomans and Syrians who were looking for money. These people brought with them European farming such as irrigation systems and mechanized equipment which enable them to thrive in an arid environment. This became the birth of Zionism, the return to Israel movement. Water rights became an issue with the indigenous Palestinian population who were mainly tenant farmers of Syrian landlords who squeezed them for all that they were worth. Unlike the North End which was an entry point for several cultures, The Palestinians were fairly isolated and lived in fear of Ottoman crackdowns, which could be severe. They viewed everyone as outsiders and of course, their lack of European technical skills put them at a disadvantage.

“T”, it would have been difficult for Jews in Imperial Russia to engage in commercial farming. Various ukases issued by the Tzar forbade Jews from owning land and banished them from their traditional cities like Odessa and Kiev to the far western reaches of the empire, an area called the Pale of Settlement. On the other hand, Zionism was a popular movement in the Jewish North End. Two of the first Zionist organizations, B’nai Zion and Chova Zion were founded in the North End and the Zion flag was designed by two North Enders, Jacob Askowith and his son Dr. Charles Askowith.

Acquiring real estate was an important aspiration for North End Jews. Owning a building in the North End offered not only an income but a sense of permanence and stability. And, if you had your name displayed on the building it advertised ones success to all who passed by. This same attitude held true for the Italians and persists to this day.

Really enjoy these historical articles. The beauty of the the North End history is that it relects what is going on elsewhere.

Nick, I thoroughly enjoyed this article. I had Jewish friends that are now deceased. It’s very sad though that today anti-Semitism has returned to show it’s ugly face.

Like racism it ( anti-semitism) never went away just went underground.

Ohabei Shalom and Temple (Adath) Israel were formed by Jews who lived in the South End. In the mid 1850s. As well as Mishkan Tefila. Do love your articles!

Thank you Nick for another well written piece of Boston History.

My Italian grandmother a non-Jew was born on Mulberry Street in the lower eastside of Manhattan. She spoke Yiddish as well as Italian and English with a NY accent. I asked my Mother why Grandma was difficult to understand at times. Mother told me that was because she peppered her English with Yiddish phrases. She took some of her girls shopping every week in the North End, arriving from 7 Border Street, East Boston where they lived on the North Ferry. I am certain her linguistic skills were put to good use at the shops on Salem Street.

The Jews did have an agrarian background. That is why a number of them settled in North Dakota.

Fargo, Grand Forks and Northern

Minnesota have cold winters and

similar field areas for farming. The

Rabbi rode a horse from town to town. There are still 400 Jewish families in the area and there is still a rabbi.

Nick, Many thanks for another fascinating story of the North End.

Nick, there is a Yiddish book store-museum in Amherst Ma. It is a fascinating place to tour. Great day trip for the Summer.

Love, love the articles, the photos and most of the comments. So much to learn – thank you for sharing!

I remember going to the dry goods stores on Salem Street…. Bed Spreads, Curtains, Table Clothes , Baby Clothes … That was when my mother or my aunt needed something quickly. My grandmother would never buy anything from a store that she couldn’t sew or crochet at home. I also remember seeing Jewish last names engraved in granite on some of the tenements. I went looking for these this year and couldn’t find them. So much has changed. I knew the North End so well, “Silvio the vegetable man”, or “Pat The Butcher” “Iacabucci’s” on Fleet street where I lived. Except for a handful of stores and the churches,… all are gone.

So are most of the people who lived here.